The forgotten extermination of Norwegians in the Soviet Union

A researcher travelled to the Kola Peninsula in Russia and collected accounts of the Norwegians who lived there. At least 27 of them were executed or died in prison camps in the 1930s and 1940s. Others died of starvation.

Millions of people in the Soviet Union were victims of ethnic cleansing perpetrated by Stalin and other Communist leaders in the 1930s and 1940s.

Less well known is the fact that a Norwegian minority of a few hundred people were almost all forced to move to other parts of the Soviet Union.

Probably one in eight Norwegians was killed or died in the Gulag labour camps.

When Mother was captured

"Mother had finished milking our cow. My little brother was still asleep as Father dressed me. When Mother started to make my bed, she turned to Father and said to him, ‘Two policemen are on their way to our house!’ Father replied, ‘So what? It could be anything…’”

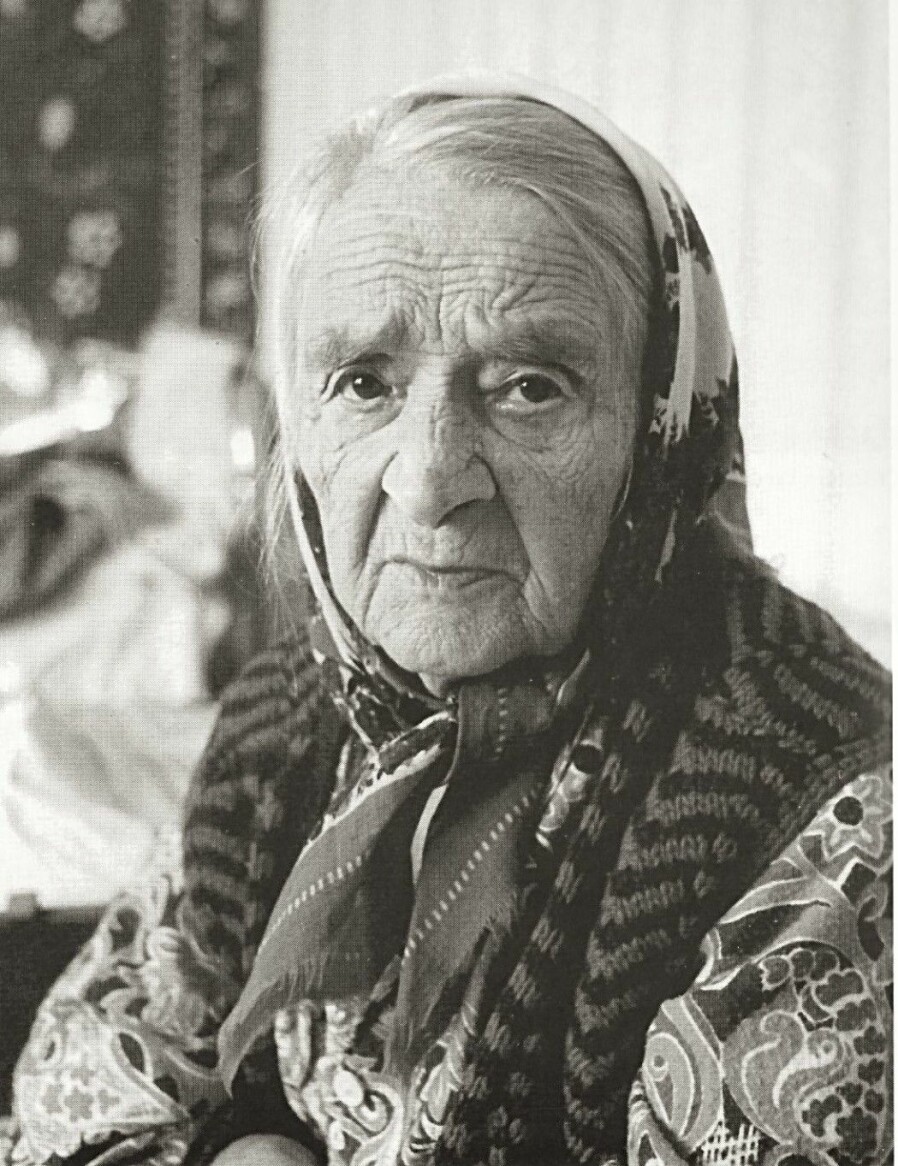

Gudrun Mironova, now called "Gidrun" in Russian, was born in 1934. She tells social anthropologist and historian Lukas Allemann about what happened when the police took 16 men and one woman from the Norwegian village where her family lived.

“Mother was the only woman. Seventeen people! As I clung to her dress, they tried to tear me away from Mother. I was screaming bloody murder, Father came over to us and gently loosened my grip. He took me in his arms and said, ‘My daughter, let's go and take care of your little brother.’

Persecution of the Norwegians

On a summer day in 1940, 104 people were picked up in the small Norwegian settlement of Tsypnavolok on the Kola Peninsula by the Barents Sea.

Their ancestors had lived there since the 19th century.

At least 17 Kola Norwegians were executed, including Gudrun's mother and grandfather. Her Sami father was allowed to remain, but was killed in battle against German soldiers a few years later.

In addition, about 25 people of Norwegian background were sentenced to prison. At least 10 of them died in captivity.

Several other Norwegians also perished from starvation and illness.

Morten Jentoft is a former Moscow correspondent for the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK) and has been interested in the Kola Norwegians for many years.

He believes – based on the premise that around 150 people of Norwegian origin lived on the Kola coast during the years of Stalin's regime of terror – that every fourth person somehow fell victim to a political judgment.

Almost half of them were either executed or died in one of the notorious Soviet Gulag prison camps.

Jentoft assumes that of the many ethnic groups on the Kola Peninsula, only the Finns were subjected to the same degree of persecution as the Norwegians. However, also the Sami and other ethnic groups were affected by the purge.

Norwegians who moved to Russia

From around 1860 and through the next few decades, Norwegian families and individuals from Finnmark county and elsewhere in Norway migrated to the coast of the Kola Peninsula in northwestern Russia.

Around 1910, the Norwegian settlement in this area was between 150 and 200 people.

Most of them did well in their new homeland. Fishing, reindeer husbandry and trade were the most important ways of life. Some people also made some money selling liquor to thirsty Russians and Sami. The Norwegians kept in touch with family and friends in their old homeland.

Following Russia’s 1917 revolution, relations with Norway declined. After the war, the Norwegians who remained on the "other side" became a forgotten part of Norwegian emigrant history.

Re-discovered in the 1990s

The Kola Norwegians were "re-discovered" in Norway in the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Jentoft says, “When I worked for NRK Finnmark in the 1980s, I heard rumours that there were some Norwegians on the ‘other side’. But no one knew anything else about them. It was only when Mikhail Gorbachev introduced glasnost and perestroika that we began to learn more.”

Jentoft remembers the incredible moment in January 1990 when, as a journalist, he met his first Kola Norwegian, Bjarne Jørstad. The Kola Norwegian spoke fluent Norwegian, a kind of old-fashioned Finnmark dialect.

Later he would meet many more Kola Norwegians.

“These Norwegians hadn’t been part of recorded Norwegian history at all!” he says.

Jentoft described it as an adventure to be able to travel around throughout Russia and find Norwegians in the most incredible places.

During the political turmoil of the 1990s, he also gained access to archives of the KGB and other Russian authorities that he hadn’t dreamt would be possible a few years earlier. There he found lots of information about the Norwegians. He also found some material in Norway’s POT (Police Surveillance Agency) archives.

In the wrong place at the wrong time

Jentoft published the book De som dro østover. Kola-nordmennenes historie (Those who went eastwards – the history of the Kola Norwegians) in 2001. Since then, some genealogists and museum people in Northern Norway have also taken an interest in these people.

But if you mention “Kola Norwegians” nowadays, hardly anyone has heard about them.

Are they in the process of being forgotten all over again? Does their history and what they endured perhaps interfere with the desire for a better relationship with Norway’s big and difficult neighbour to the East?

Jentoft thinks we should be a little cautious about using the term "ethnic cleansing" for what happened to the Kola Norwegians. “They lived in the wrong place at the wrong time. The traditional Russian suspicion of foreigners was probably also part of the reason for why the Norwegians were subjected to Stalin's Great Terror.”

These people who had settled along the cold and relatively uninhabited coastline at the far end of the Barents Sea in the latter half of the 19th century – about as far away from civilization as it was possible to get – were, a few decades later, thrown into world history in a way no one could have imagined.

“They experienced a lot that was terribly dramatic,” says Jentoft.

“First came the Russian Revolution. Then they became part of the great social experiment of the Soviet Union, creating history's only Norwegian collective fishery, called “Polarstjernen" (Polaris). Then came World War II. The remote area where they lived became one of the key sectors of the front during the war between Hitler-Germany and Stalin's Soviet Union."

Individual stories

Lukas Allemann is a social anthropologist and historian at the Arctic Center, University of Lapland in Finland.

He uses the oral accounts of individuals to show us the history of the ethnic minorities on the Kola Peninsula.

“The Norwegian community on Kola was completely destroyed. People were either shot or deported. Nothing was left of it,” says Allemann.

“This destruction was extreme even by Stalin’s Great Terror standards.”

The researcher believes that by listening to the life story of a person like Gudrun Aleksandrovna Mironova, we can discover how individuals managed to find their own strategies to cope with the great difficulties created by the larger society.

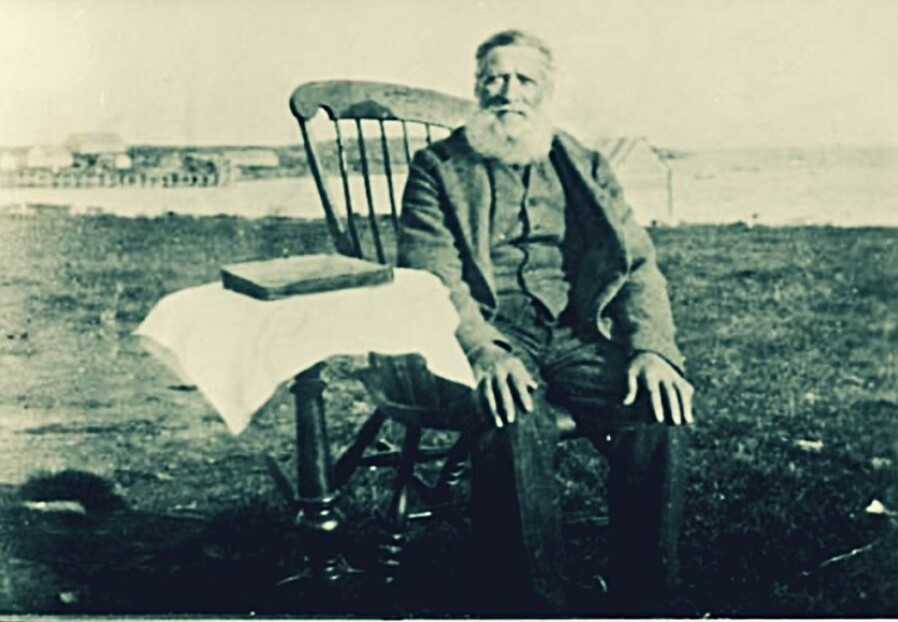

Gudrun's parents had moved east from Norway in the late 1800s.

Whereas several Norwegians who did the same settled in Tsypnavolok, Gudrun's forebears chose to settle in Drozdovka, a coastal village a little further east. There her parents had 13 children.

The family owned several fishing boats and lived in a two-story house, indicating considerable prosperity for the times.

Gudrun's mother Gudrun Margaret Fredriksen had married Aleksandr Petrovich Zakharov, a Russian Sami.

Norwegian resistance

Allemann is interested in the resistance that minority groups like Norwegians and Sami in the Soviet Union were able to show against the totalitarian state.

“The history of people like this has often been that they became passive victims of a totalitarian state. But that’s not always true,” says the researcher.

The Soviet campaigns against self-sufficient farmers and fishermen hit the Norwegians on the Kola Peninsula hard. In 1930, the fishing collective Polarstjernen was forcibly formed in Tsypnavolok. All the Norwegians in the village had to give up their boats and equipment for collective use.

“The Norwegians in Tsypnavolok clearly expressed what they thought of this,” says Allemann.

Humanizing the oppressors

At the same time, the researcher observes how Gudrun, a victim of Stalin's terror regime, is also capable of humanizing the oppressors. That is another strategy a person can choose to use.

She tells the story of how the militia that had been sent to their Norwegian village to oversee them found their role unpleasant.

She does not simply describe these oppressors as faceless "others."

Allemann was also struck by how the Norwegian village supported Gudrun's Sami father Aleksandr after his wife was taken away. Not long afterwards however, he was sent to war for the Soviet Union and killed in battle against the Germans.

Gudrun and her brother Sasha thus grew up as orphans with relatives in the Kola village of Kanevka.

Later, Gudrun found a job as a cook in a Soviet military base on the Barents Sea coast. After an accident, she pursued her education, becoming first a secretary and then a nurse.

But not until the 1950s did anyone dare tell Gudrun what had happened to her mother and grandfather: that they had been shot. And that she should not tell anyone about this.

Uncle Ludvig escaped

The researcher also hears about Gudrun's uncle Ludvig:

"He never married. They pursued him. So every three months he used to change his place of residence, travelling back and forth along the whole coast. Once, a policeman said to him: ‘You know, you're a good guy. Change where you live every three months. Before they find you, you'll already be in a new place.’"

What the friendly officer was hinting at is that if Ludvig took into account how slowly Soviet bureaucracy moved, he could fool it by constantly staying ahead of those who were trying to track him down.

Also in Stalin's Soviet Union it was possible to become a man who did not exist.

According to Gudrun, the policeman had understood that Ludvig was just an ordinary man and not a Norwegian spy.

In this way he may have helped save Ludvig’s life.

Norwegians sent to Karelia

Gudrun also points out that several of the Norwegians might well have survived Stalin's terror, since some of them were deported to the Russian-Finnish area of Karelia.

There hadn’t been any Norwegians living in Karelia before.

Thus, probably quite a few Norwegians disappeared "under the radar" of eager participants in Stalin's purge of minorities. The Soviet bureaucracy's lists of who and how many were to be taken were based on censuses and statistics from the 1920s.

Since Norwegians did not appear in the statistics, Gudrun believes there was also no persecution of them in Karelia. There it was usually inhabitants of Finnish descent who were branded as "spies."

Several of the Norwegians who were first sent to Karelia, were later sent on to the small place of Tarza far in the forests south of Arkhangelsk. Many died of hunger and malnutrition.

Little people's stories

Lukas Allemann worries that individual biographies like this one may disappear if historians just give us the big stories.

Researchers need to have conversations with people who have experienced something, or whose descendants have, before we lose them.

Otherwise, we may not understand important parts of our history.

The usual tale of the Great Terror of the Soviet Union in the 1930s is often about how well-organized the process was. Individuals were just “raw material” for powerful and cynical political actors in Moscow.

"But Stalin's terror regime was far less systematic than we tend to imagine it," says Allemann.

“There was a lot of chaos. Things happened fast. Quotas were issued on how many people to kill or deport. Pure coincidence often determined who lived and who did not.”

Social warmth

By listening to individuals’ own stories like Gudrun's, we hear how a person and those closest to her arranged their lives in the face of such horrors.

They were not just passive victims.

Allemann believes that these particular stories may have made it easier for Gudrun to cope with the trauma she experienced as a child, when her mother and grandfather were taken from her and executed, and her father was killed not long afterwards.

Gudrun “counterbalances past atrocities with pride, the brutality her family faced with the social warmth and human kindness that was also present in the community around her,” says Allemann.

"She counteracts the oppression with the fact that people were still able to act, to live".

Allemann thinks researchers, journalists and aid organizations often tend to look at victims solely as victims.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Gudrun has received many visitors, including Norwegians and Sami activists, some of whom may have been “one-sidedly looking for downtrodden victims of an oppressive regime,” he says.

The victim as a social construct

Gudrun, like other descendants of the Kola Norwegians, was offered the opportunity to settle in Norway after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Numerous people accepted this offer, including some of Gudrun's relatives. But Gudrun chose to stay in Russia.

Allemann points out that the victim role is often a social construct.

“Had Gudrun moved to Norway, perhaps other discourses and a different life trajectory might have framed her memories of oppression and agency differently,” he says.

References:

Morten Jentoft: “De som dro østover. Kola-nordmennenes historie” (Those who went eastwards. The history of the Kola Norwegians), Gyldendal, 2001.

Morten Jentoft's book about the Kola Norwegians has been printed in six editions. The author has now had another edition printed at his own expense. The book can be ordered by sending him an email: morten.jentoft@nrk.no

Lukas Allemann: "I should never tell anybody that my mother was shot: Understanding personal testimony and family memories within Soviet Lapland," Oral History, Fall 2019.

Terry Martin: "The Origins of Soviet Ethnic Cleansing," The Journal of Modern History, vol. 70 (4), 1998. Article.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no